Asakawa Family, Pavilion Caretakers

Legacy of the Asakawa Family

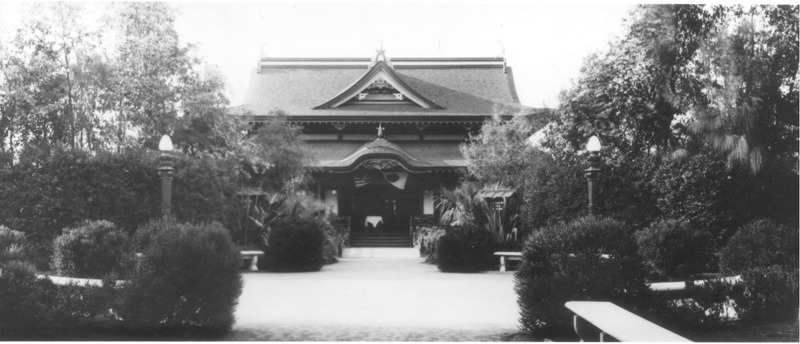

At the conclusion of the Panama-California Exposition, the architectural group Watanabe and Shibada gifted the Tea Pavilion to the City of San Diego. [1] In turn, the City then leased the building to Asakawa Hachisaku and his wife Osamu, assisted by a cousin Asakawa Gozo. Their family cared for and managed the teahouse and gardens from 1917, through the 1935-36 Exposition -- continuing for twenty-four years until 1941. [2]

“After the Panama-California Exposition closed in 1916, the City of San Diego decided to ask a local Japanese couple to run the tea house. My mother wanted to try running a business, so we moved into tiny living quarters at the back of the tea house.

After we opened the teahouse to the public, we sold tea and noodles, and served them on the porch that surrounded the building on three sides. My mother created green tea ice cream by mixing the tea powder into the ice cream. Inside there were traditional tatami mats made of bamboo on the floors, and my mother had a small gift shop where she sold small things imported from Japan. In later years, there were beautiful wisteria arbors in the garden, and a Japanese photographer took a photograph of my mother in her kimono, posing in front of the wisteria.” — George Asakawa [3]

Born in 1915, the first year of the Panama-California Exposition Moto Asakawa lived in the teahouse after their family took over its operation and caretaking in 1917. Due to limited living space, Moto and his brother George slept in the unfinished attic above the main teahouse. As they got older, the brothers helped maintain the garden, including pulling weeds, thinning giant bamboo stalks, and harvesting bamboo shoots. Other tasks included replacing the rice paper of the many sliding shoji screens every year because locals persisted in poking their fingers through it [3].

The Asakawa's also operated it as an exhibit during the second Exposition held in 1935-36 and afterward until 1941. With the United States' entry into World War II and President Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1942 Executive Order 9066, the Asakawa's were forced to leave thier home - along with approximately 120,000 other Japanese-Americans sent to internment camps [4]. The American Red Cross took over the teahouse and its grounds during WWII, and it became a personal lounge for the Naval Hospital until 1946. It then fell to disrepair, boarded up and eventually demolished [1].

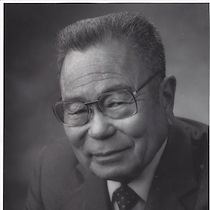

Although Moto and his family eventually returned to San Diego to begin anew after the internment camps were closed, they never saw their old home again [5].

The legacy of his family would prove to greatly influence Moto in his later life. In 1950, Moto established the Presidio Garden Center. By 1970, he had also become active within the California Association of Nurseries and Garden Centers (CANGC), even serving as President from 1975-1976. Moto also helped establish the California Certified Nursery Professionals program and the CANGC's Endowment for Research & Scholarship, with an endowment of three million dollars which funded students and researchers in the field of horticulture. Within the community, Moto was also a founding member of Kiku Gardens, a senior citizens' retirement home, twice President of the San Diego Japanese American Citizens' League, as well as an active supporter of the modern Japanese Friendship Garden at Balboa Park. [6]

Works Cited:

[1] Amero, Richard. "A Panama-California Exposition: A History of the Exposition." Panama-California Exposition. San Diego History Center. https://sandiegohistorycenter.org/archives/amero/1915expo/

[2] Estes, Donald H. “Before the War: The Japanese in San Diego.” Journal of San Diego History

San Diego Histroical Socety Quarterly, Fall 1978, Volume 24, Number 4. Editor Thomas L. Scharf. San Diego History Center - Our City, Our Story, September 30, 2016. https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1978/october/before/.The

[3] “Our Past.” Origin of the Japanese Friendship Garden After the World Exposition. Japanese Friendship Garden San Diego, n.d. https://www.niwa.org/past.

[4] “Chronology Of Japanese Americans in San Diego: 1885-2010.” Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego. JAHSSD, 2021. https://www.jahssd.org/timeline-1885-2010/.

[5] Canada, Linda A. Archivist, Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego. JAHSSD.

[6] San Diego Union Tribune. “Moto Asakawa Obituary." San Diego Union-Tribune. December 8, 2011. https://tinyurl.com/a7pck2fx.